August 12, 2022 by Sarra Cannon

Our discussion of how to write great scenes continues today with Episode 4 of the series, where we’ll be going over scene structure. This is really where everything we’ve talked about so far comes together to create the true building blocks of your entire novel or story.

If you missed the first three parts, I’ll link them below so you can catch up!

Episode 1: How To Write Great Scenes That Keep Readers Engaged: Writing Great Scenes #1

Episode 2: Your Character’s Goal or Desire In A Scene: Writing Great Scenes #2

Episode 3: How To Write Conflict: Writing Great Scenes #3

Earlier, I mentioned that in some ways, each scene is a mini-story within your book. As the reader progresses from one scene to the next, so does your character’s journey from who they are at the beginning of the story to who they need to become or what they need to accomplish.

In many ways, scenes mirror the overarching story. Your character will usually have a goal that becomes the main focus of your entire story, but your character will also have a smaller goal in each individual scene. In the same way, there will often be a larger, story-level conflict in your book, while each individual scene will also contain its own smaller conflict.

The progression of the scene-level goals is what makes up your character’s journey toward the larger story goal, kind of like breaking their larger goal into steps along the path.

The same is true when it comes to story structure in a scene. While we’ve all learned that a novel-level story structure contains a beginning, middle, and end, the same is true for your scenes, so today we’re going to go into what happens inside this micro-story structure and how to apply that to your own writing and story planning.

The beginning of your scene will often contain some kind of hook, just like the beginning or opening chapter of your novel contains a hook. Often, this is just a single interesting sentence or opening paragraph that draws the reader into the goal, stakes, or action of this scene.

You can achieve this with action, surprise, emotion, intrigue, any number of tools, but the key is to ground your reader in the who/what/where of the scene as quickly as possible, while also clueing us in to what’s at stake or what our character’s desire is for this scene.

Remember that we spent all of Part 2 talking about your character’s goal in a scene? This is where you’re really going to apply all of that knowledge. Let the reader know what your character is after in this scene. Is it something they want to accomplish, obtain, do, understand?

Then, remind us what’s at stake if this character fails or doesn’t obtain their desire in some way. What are the possible dangers or consequences to our character or the story at large if things don’t go our way here?

Opening with a hook and introducing your character’s goal and what’s at stake if they fail right from the first page or two of your scene is often one of the best ways to draw readers into the scene and keep them engaged.

Once the scene has begun and the reader knows what’s going on and what’s at stake, it’s time to really develop the conflict. This, of course, was our entire focus for Part 3 of this video series, so if you haven’t watched those earlier videos or you’re just joining us, I highly recommend you head back to watch them (they’re linked above for you).

The conflict in a scene is basically the obstacle to your character’s goal. What’s standing in their way of getting what they want?

This conflict is usually going to be the main event when it comes to the middle of your scene. Your main character will be taking whatever action they have decided to take in order to achieve their goal or desire, and as the scene unfolds, something is going to stand in their way.

The conflict can, of course, come into play in that very first hook sentence in a scene, but the real meat of the scene will further develop that conflict and our character’s attempt to achieve their goal or desire.

The end of the scene is usually going to be where we see the outcome of the goal and conflict for this scene. In many cases, the outcome is not going to be the one our main character was hoping for, because as we talked about earlier, if your character just sails through your story, always getting everything they want and all their plans going perfectly, you’ve got a pretty boring story on your hands.

The end of the scene is where, many times, the conflict of the scene is resolved in a way that keeps our main character from achieving their desire or goal. Also, the action of a scene can be most powerful when the stakes we thought we understood at the beginning of the scene get raised or become even worse than we imagined.

Just like with our discussion of scene-level conflict last week, the outcome or ending of a scene can contain a true disaster or major consequence, or it can be a subtle, more understated loss that keeps our main character off-balance or wondering what they’re going to do now.

I forget exactly where I first heard this term to describe the ending few words or moments of a scene, but it really stuck with me. I believe it must have been Libby Hawker’s Take Off Your Pants, but I believe I’ve also heard James Scott Bell use this term of a “cymbal crash” at the end of a scene.

Basically, what we’re talking about here is a statement or zinger at the end of your scene or chapter that resonates with your reader. It hits them in the gut and makes them feel something deeper, or it leads them into that next chapter or scene in a way that they literally cannot resist turning the page.

My readers love calling this the “dun dun dun” moment, and it’s pretty much how I end all of my live readings. So much so that they’ve come to be able to predict where I’ll leave off for the day by just how big of a “Dun dun dun” moment it is.

So, let’s look at these elements in terms of an example. In my book, The Witch’s Key, a teen girl named Lenny has recently lost her demon-hunting parents and been forced to move to a new town to live with her Uncle Martin, a man she barely knows.

In this scene, it’s Lenny’s first day of school. She’s basically been a hermit all summer and has never had to go to normal public school, so she’s totally out of her element here. From the first couple of sentences, we understand her goal.

Twenty minutes later as I stood in front of the doors to Newcastle High, I felt nearly invisible. Just like I wanted.

Lenny’s goal: To be invisible and not stand out at all on her first day at school.

Stakes: The stakes at this point are completely emotional. In the first few chapters, we know just how hard of a time Lenny’s had and how much she’s hoping to just blend in with a bunch of normal kids and not have to deal with the magical dangers that got her parents killed.

As we move into the middle, or action, of the scene, the conflict starts to appear.

Everyone who walked up smiled and greeted friends they’d probably had since preschool, but no one seemed to notice me at all.

My spell had worked. I’d used just enough amaranth to help me blend in, but not enough to make me completely invisible. Hopefully, this would make high school a lot more tolerable.

I would show up, do whatever I needed to do to survive it, keep my head down, and that would be that. It was just one year, after all.

I took a deep breath and told my feet to start walking, but I couldn’t seem to force them forward. Literally every single muscle in my body was rebelling against the idea of high school.

“It’s not as bad as it looks,” a bubbly voice said out of nowhere.

At first, I assumed she was talking to someone else, but then this small, energetic girl was suddenly there, smiling up at me like we were old friends.

Okay, so here’s where the conflict starts for Lenny. Her spell worked, but this girl noticed her anyway. Did she see through the magic? And if so, what did that mean? As the scene progresses, the conflict increases as we learn a piece of information that hints at the larger conflict of the entire novel.

“We all have to stick together right now with everything that’s going on,” she said, her eyes looking downward.

“What’s going on?” I asked.

“It’s just terrible, isn’t it?” she asked, all the joy drained from her voice. “I can’t even bring myself to talk about those girls. Nothing like that has ever happened in Newcastle before. No one really knows how to deal with it.”

So, Lenny learns here that not only is she not invisible like she hoped, there’s potentially magical people here in Newcastle and there are girls who are missing or possibly even dead. This is the kind of mystery her parents used to look into all the time, and it’s exactly the kind of thing that got them killed. Lenny wants no part of it.

This is what leads us into the end of the scene, where she realizes that her dream (or goal) of just blending in and avoiding any kind of magical life for the moment is completely hopeless.

I started to put in my combination, but before I was finished, a chill ran down my back that was so strong, my entire body shivered.

I stopped breathing for a moment, my hand stopping completely as I focused on that feeling. It was the last thing I had expected to feel here today in a town like this.

Martin had said everyone in this town was human. Normal.

Mostly, he’d said. They were mostly human.

“Do you need help?” Peyton asked. “Here, I can show you how to do it. I remember the first time I…”

I tuned her voice out for a moment and slowly turned around, searching every single face in the hallway. My heart raced, and I hardly allowed myself to take a breath as I scanned the room.

That feeling had come from someone here. Someone close.

And then, suddenly, there he was.

He was tall. Over six feet, if I had to guess.

His dark hair was just long enough to fall across his forehead, but not so long that it covered his dark, serious eyes. His tanned skin practically glowed with the health of immortality, even under these crappy, fluorescent lights.

He was strong, too, judging by the muscles that strained against the sleeves of his grey t-shirt.

But most importantly, there was a certain energy about him that I’d come to recognize over the years as…other. This guy, whoever he was, was not human.

And he was staring straight at me.

Do you hear that cymbal crash at the end of that scene? I could have just ended it with him not being human. That could have some level of resonance, sure, but it’s the fact that he’s staring right at our heroine that really packs a punch and hits you in the gut as a reader.

She doesn’t just sense his presence, he can sense hers, too. Definitely a disastrous outcome for a girl whose goal was simply to be invisible here in her new school.

When we get to the end of a scene, there’s often another piece of it that contains our main character’s reaction to what just happened. Jack Bickham calls this Scene and Sequel.

A sequel is a beat after the main action of a scene where your character has a moment to slow down, process what’s just happened in the scene and then decide what’s next. Often, this can be an emotional beat or a moment of character development, where your character asks themselves what does this mean about me? Where do I go from here?

Some authors call this moment a recalibration or a reaction. It can be a moment of introspection or a conversation. It can be a few lines or it can take up an entire chapter, but this sequel beat doesn’t exactly follow the same structure as a scene.

In KM Weiland’s book, Structuring Your Novel, she shares that while scene structure is about goal, conflict, and disaster (or outcome), the sequel’s structure is about reaction, dilemma, and decision. This means your character has a moment to react to what just happened in the scene, realize what this means for them in terms of their goal, and then make a decision about what they’re going to do next.

I don’t necessarily have a sequel for every single scene in my books. Part of this is because I write multiple-POV. I like to leave a character with a cymbal crash moment and then switch to the scene of a new character. Often, my sequel moments will be short or just a few sentences of reaction or emotional introspection. Sometimes, though, if my character needs to totally recalibrate, take stock of all the current obstacles to their path and make a new plan, I’ll have an entire chapter or two that aligns with this idea of a sequel.

Now that you’re aware of it, I recommend reading and watching shows or movies and trying to identify these sequel moments. It’s the kind of thing where your villain comes in and threatens the heroine as she’s tied up in his dungeon, but the second he leaves, the heroine has a moment of processing what he just said and coming up with her next move.

It can also be a moment where something intense has just happened and your character’s really shaken by it so they duck into a bathroom and splash their face with water as they process what just happened.

That’s a sequel, and you’ll start to see them everywhere as a tool for pacing and character development.

It’s also fun to pay attention to how really great writers keep the tension up during these types of reflection scenes. It can be subtle, but it’s often tied into the main character’s fear or worry in some way or the reader’s anticipation of just how bad things are about to get.

Now that you understand the structure of a scene, it will hopefully be easier for you to now fill out your scene cards or notes on what’s happening as you begin to build your story, scene by scene.

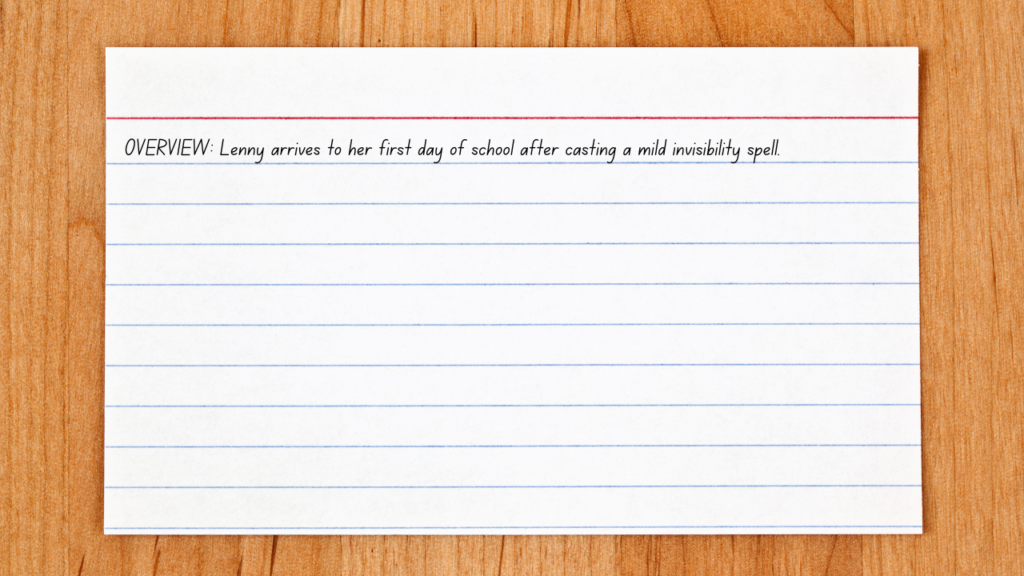

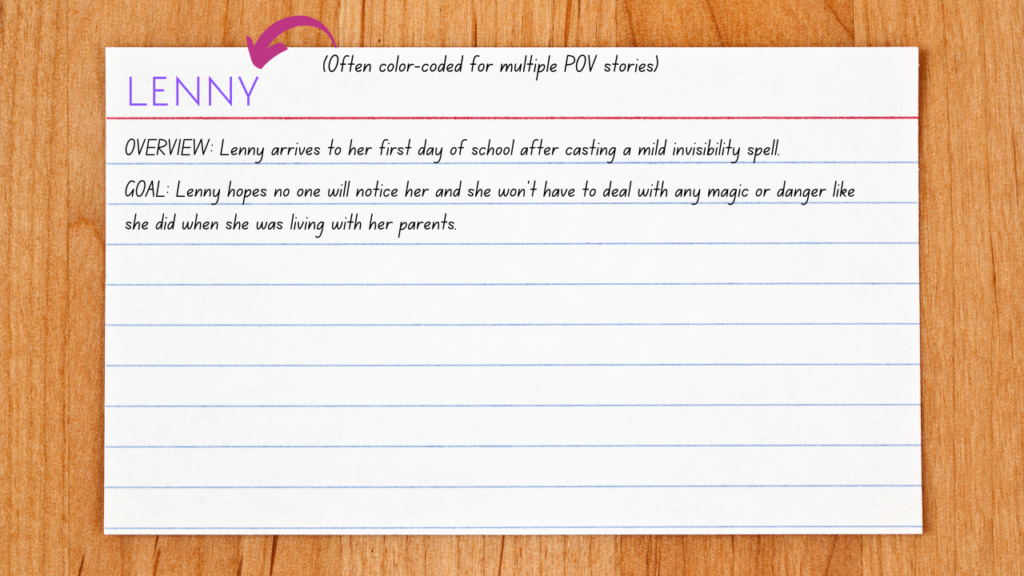

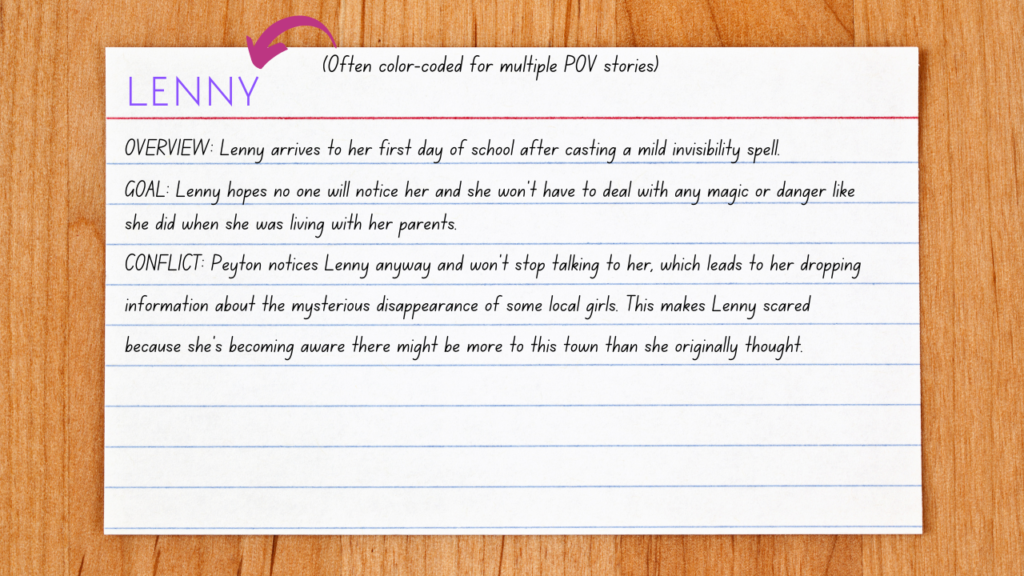

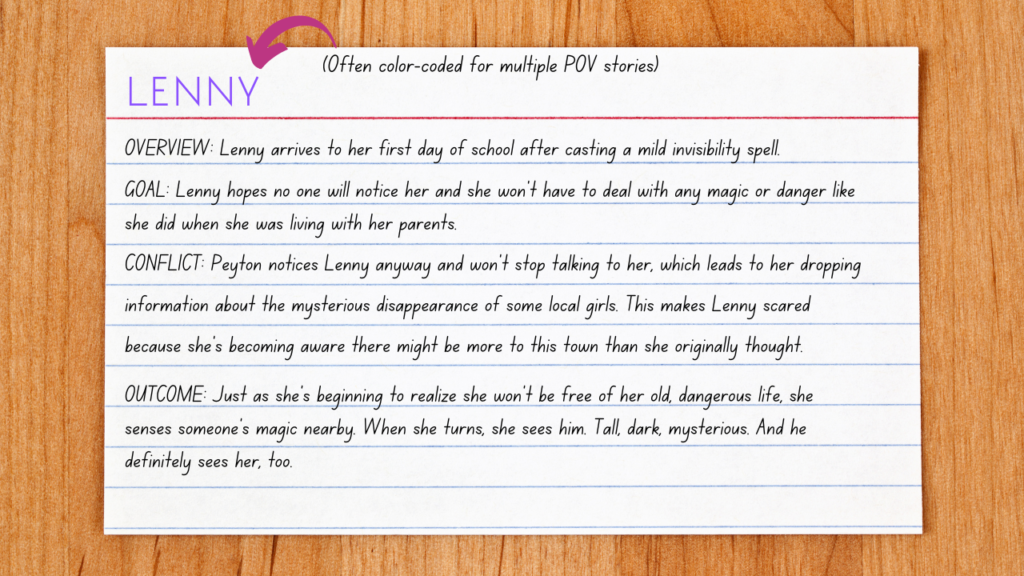

In your workbook, you have an example of the way I fill out my scene cards, and it looks something like this.

Here’s another chance to grab the workbook if you haven’t already!

At the top, I’ll often write just a single sentence about the main action of the scene. So, for The Witch’s Key example above, I would have written something like, “Lenny arrives to her first day at school after casting her light invisibility spell.”

Next, I will list my POV character, their goal, and any notes about what’s at stake for them if they fail. From our example, I would maybe write, “Lenny hopes no one will notice her and she won’t have to deal with any magic or danger here at school like she did when she was living with her parents.”

Just this simple sentence tells me how this scene is building on what we already know about Lenny from previous scenes. It’s also telling me what her desire is and hints at her emotional stakes.

Conflict is the next focus on my scene cards, which is basically just the main action as the scene develops. “Peyton notices Lenny anyway and won’t stop talking to her, which leads to her dropping some information about the mysterious disappearance of some local girls recently. This makes Lenny scared, because she’s becoming aware that there might be more to this town than she originally thought.”

Finally, at the bottom of the scene card, I like to state the outcome, or as KM Weiland calls it, the disaster. For this scene, I’d write, “Just as she’s beginning to realize she won’t be free of her old dangerous life here, she senses someone’s magic nearby. When she turns, she sees him. Tall, dark, mysterious, and he definitely sees her, too.”

If you can clearly write down your character’s goal, why it matters to them, what’s going to happen in this scene that stands in the way of that or puts their desire in danger in some way, and the outcome of the scene onto a card, it will practically write itself.

The other cool thing in planning your scenes this way is that it quickly becomes clear what you need to decide next as an author to move your character and story forward. That’s what we’ll talk about next week in Episode 5.

I sincerely hope you’re enjoying this series about writing great scenes. I find that sometimes the combination of examples and instruction can really help it hit home, so let me know if you’ve enjoyed it and would want to see more examples in the future.

Next week, we’ll go over how you take the big picture view of a novel’s plot and break it down into scenes that have proper pacing. It’s going to be fun! I’ll see you there.

I have been self-publishing my books since 2010, and in that time, I've sold well over half a million copies of my books. I'm not a superstar or a huge bestseller, but I have built an amazing career that brings me great joy. Here at Heart Breathings, I hope to help you find that same level of success. Let's do this.